This text is conceived as a diptych: two panels in tension, written at different times but held together by memory. The second part reflects on the first not to correct it, but to acknowledge the emotional truth of what was once believed, before history complicated the story.

…and even the noticing beasts are aware that we don’t feel very securely at home in this interpreted world (Rainer Maria Rilke)

Part I: Mnemosyne

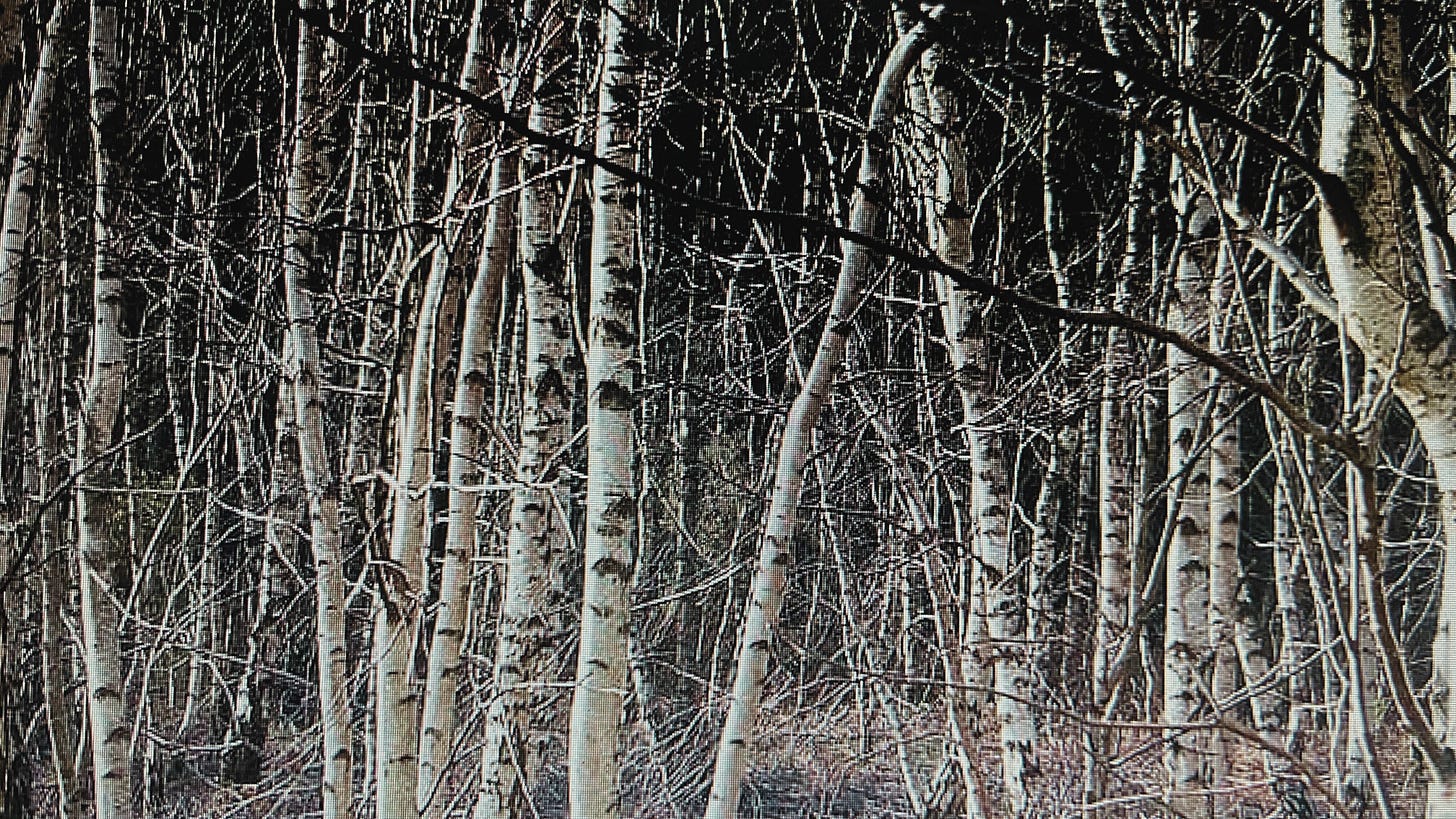

In a corner of my grandparents’ garden there was a giant birch tree - slender as it was it spat out its roots. Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, was reluctant to settle here. The birch a lone rebel rejecting the alien soil, enduring the same homelessness as its planters. Its soul still subscribed to heaven, and the gradual descent towards human affairs was painful and profane. For their grandchild, this birch tree became a most sacred space. My spiritual home. My grandparents called their spiritual home Riga- a paradise lost that I connected with while climbing up to the top branches. As if this Riga would materialise from a higher viewpoint, embrace us expellees and take us home.

The world outside the garden was enemy territory, a minefield that the grandchild skilfully traversed. In winter, I pretended my grandmother’s fur coat was my armour. A magic coat. This fur coat helped her survive on her escape, kept her children warm and connected her to her previous life in Riga. Our family was different, my grandparents were ostracised, their agitating neighbours opposed my grandparents with passion. Their surname, Steinblum, was enough to hate them as “those who escaped the destiny they deserved”.

Wortmann’s, the grocery shop, became another battleground. When my grandmother and I arrived, the shoppers became silent and observed my grandmother suspiciously. So violent a silence. As poor as my grandparents were after the war, my grandmother could not shed her upper-class upbringing with the same ease with which she shed her fur coat in winter. I remember how these merciless villagers ended the silence in a sea of whispers, which became louder and more comfortable, the further we walked away.

“I wonder why these ones were forgotten by Hitler?”

“How can these have-nots still pretend they are special?”

Their words were knives in our backs. I never understood what these people were proud of, how being born into the German province could offer them any satisfaction. Their envy was sticky and black, hot and viscous tar.

This Baltic birch was as laden with nostalgia as the amulet of my great-grandmother Bella and my grandmother’s fur coat, two of the few possessions rescued. Sacred family totems that were linked irreversibly to the many things lost – family members, graves, memories, and stories that contained the lost world of my family. The amulet was my Aladdin’s lamp. As soon as I opened it, my senses sharpened to the immaterial membrane that alienated us from others. Through its magic, long-dead family members talked to me, shared their lives and accepted me as their storyteller.

The things lost represent the resilience of the refugees. What was irretrievably gone fascinated me much more than the reality of the German province in which I grew up in the 1970s. Nostalgia became the sentimental language to share what vanished, to mourn an absence that was too cruel to talk about. Sometimes stories need no words to emerge.

My mother inherited my grandmother’s elegance but refused to trust it. Belonging to the village was safer, became her relief from pain and loneliness. Belonging means knowing what to choose and holding it dear. My mother’s choice muted the past. She collected her wealth to silence Mnemosyne. She rejected the fur coat as too old-fashioned an item and downplayed its importance for her survival.

Tantalus committed such an atrocity against the gods that his descendants were cursed forever. His guilt was inheritable, his descendants’ terrible misfortune attributed to the crimes of the ancestor. Our family story was interlinked with the horrors of the Nazi times, the terror and the bloodlands of Nazi super elevation that devastated Europe and claimed more victims than any war before. The fur coat of the refugee was interlinked with the fur coat of the deported. Shocking images of absolutely terrified Jewish women in their fur coats at the ramp of the concentration camp in Auschwitz. Piles of these coats were later the only reminder that these women had existed. When my grandmother watched these images later in life, her face became a mask.

During the war, silence was mandatory to not accidentally expose the family secret. My mother was born into it and never longed for another truth. Even today, she does not want to know. As her eldest daughter, I was obsessed with the past but was not wise enough to ask the right questions, and I was too immature to cut through the thicket of imposed silence. While Germany embarked on its culture of commemoration, my family forgot. We forgot and remained trapped in what could not be expressed. My grandparents died while I was a teenager. Riga and the past became echoes. My cold family drifted further apart. Overachievement was their way to forget and obey. My father’s mother and her appalling absence of guilt overwrote the painful silence of the victims in my maternal family with her narcissistic refusal to take any responsibility. My mother would tirelessly serve her to find acceptance in the most unlikely place. Futilely.

Only Tante Gisi, my mother’s elder sister, knew and shared her memories with me. During the Nazi time she was constantly questioned because she looked Jewish. In Nazi Germany, the Ariernachweis, the Aryan certificate was a document which certified that a person was a member of the presumed superior Aryan race and not of Jewish descent. Our family origin became Swedish as in the crude Nazi ideology Swedes were recognized as Aryans. Steinblum became Stenblom. Being Swedish was accepted and internalised. The forged certificate allowed survival. Survival in wolf’s clothing. My aunt remembered the fear and the obscurity of identity, while my mother inherited the dense silence and blond hair that no one else in her family had. She was safe.

My grandparents’ son Wolf was killed in a car accident after the war, when the suffering should have ended. My Onkel Wölfchen was only eight years old. As a child, I often visited his grave together with my grandmother. He remained a child forever and had to compete with all the previously gone family members. His grave became a place also to mourn those family members whose graves had been left behind in a realm that the post-war Iron Curtain turned into a paradise lost. Nameless family victims killed by the war and forgotten in the relentlessness of time.

When the Iron Curtain was lifted, I often travelled to Riga. My sacred place became a real place, my family’s home and their summer house had new owners and remained alien. The longed-for paradise became a prop for my grandparents’ life without any deeper meaning for me. In front of their house, I could finally cry those dry tears and mourn the long-ago cutting down of my sacred birch, which marked my final expulsion from paradise when I was a teenager.

The reluctant storyteller that I am, only recently asked what happened to my grandmother´s grey Persian lamb coat. After her death, it disappeared. As if the alienness of the stranger could be undone when her disturbing objects of ambivalence have been seized. Vanished, like the birch tree that no longer rises into the sky.

PART II: The Erinyes

This text is conceived as a diptych: two panels in tension, written at different times but held together by memory. If Mnemosyne speaks from within the spell of silence and longing, the Erinyes carry the unease that follows, the slow stirring of doubt, the ancestral whisper that something is being withheld.

Like the ancient Furies, the silence did not rest. It pursued. It pressed. It became a presence in its own right, reminding me, the want-to-be storyteller of the family, that something was unsettled. Behind the myth of innocence, a path may lie not only lost but also deliberately obscured.

To want to be a storyteller is to commit to truth, to the pain of unlearning, and to the burden of saying what was never meant to be said. The Erinyes have made me feel, again and again, that I must choose between love and betrayal. That telling the story might mean losing the people I love, not literally, but emotionally. That clarity might cost belonging.

I once believed that we had only suffered. That we had been merely exiled, not involved. The emotional truths I wrote about in Mnemosyne —the garden, the fur coat, the imagined paradise of Riga —were shaped by that belief. But in time, a deeper reckoning began. A need to question the silence that defined my family’s past, and to ask what that silence protected.

At school and in the German village, people often remarked, sometimes with suspicion, sometimes with disdain, that Steinblum was a Jewish name. Teachers, neighbours, and other children made sure we knew. My grandparents never addressed it. They never spoke of ancestry, nor did they correct or confirm the assumptions made about them. They simply stayed silent.

As a child, I interpreted that silence as meaningful. I thought, perhaps, there was something to it, some hidden truth, some trace that made us different. That idea once comforted me. It allowed for emotional distance from the history I would later uncover. If we had been mistaken for Jews, maybe we hadn’t been on the side of the perpetrators after all.

Much later, during my research, I did find Jewish Steinblums in Riga. Perhaps they were relatives, but we do not know. Riga was a diverse and layered city, with Latvian, Russian, German, and Jewish citizens. Even though there were clear dividing lines, the city was shaped by coexistence. Names, languages, and lives overlapped, sometimes uneasily, sometimes closely, in ways later histories have often flattened or forgotten.

There is no trace of those Jewish Steinblums in our family records, nor is there any mention in family stories. And in any case, my grandparents had the correct papers. They were Germans. And during the war and resettlement, they made the choice and integrated themselves into the Nazi system.

In the archives, I found fragments that shifted the story: not a dramatic revelation, but a slow accumulation of contradictions. My grandfather, once remembered as a gentle presence, appeared in Nazi personnel files not as a significant figure, but as someone who participated. Someone who remained. Someone who did not say no.

This is where the Erinyes whisper: not to accuse, but to remind. To make forgetting impossible.

I wrote in my research that we, the later-born, do not inherit guilt, but we inherit silence. And in families like mine, silence is not empty. It is heavy. It carries the weight of what was never spoken and what was never asked—the warmth of family memory clashes with the cold, bureaucratic nature of the archive. The tension between them cannot be resolved; it can only be acknowledged.

Writing this has felt like both an act of betrayal and an act of love: love for my family, for the truth, and the future. It has forced me to confront what it means to write about complicity within one’s own family and to bear the discomfort of uncovering histories never meant to be spoken aloud. But history is not merely about the past; it is about the present, about how moral responsibility, memory, and the long shadows of violence continue to shape us.

Silence is not an absence. It is a presence, dense with everything we were not supposed to see. To want to be a storyteller is to carry responsibility not just for the past, but for the future. Even when it feels like betrayal, it is an act of love for those who come next.

As a narrative therapist, I often work with people who are trying to make sense of the stories they’ve inherited—the ones that were told, and the ones that weren’t. If this piece speaks to something you’re grappling with, you’re very welcome to get in touch. I’d be glad to accompany you in exploring what memory, silence, and responsibility might mean in your own context.